- Published 23 Jan 2023

- Last Modified 29 Aug 2023

- 11 min

A Complete Guide to Hard Drives

Read our hard drives guide, explaining their uses, how they work, the different types, capacity, cost, and brands.

Reviewed by Mithun Subbaroybhat, Technical Support Engineer (December 2021)

What is a Hard Drive?

So, what is a hard drive? Broadly speaking, computers employ two types of data storage, and these could loosely be described as active memory and passive memory.

RAM (Random Access Memory) is the active kind. It is used to store and run the code that the computer is currently deploying, such as the applications you have opened, and the operating system features you are using. It is called random access because the computer can access this data in any order and at very high speeds.

Meanwhile, hard drives could be described as passive memory devices. They store data for later retrieval and use in RAM. Traditional hard drives are direct access rather than random access, meaning that the physical location of the data on the device will affect its retrieval speed.

Modern hard drive technology is mounted directly onto circuit boards rather than being a standalone component. By contrast, external or portable hard drives are entirely separate devices, usually connected to the computer via a high-speed data cable.

Uses of Hard Disks

Hard drives have one central use - the storage of data for later retrieval. They store three kinds of data:

- The operating system - e.g. Windows, macOS, Linux. These complex software architectures act as an intermediary between the hardware and the user, allowing the computer’s full capabilities to be deployed

- Applications, also known as programmes - everything from Google Chrome to Adobe Photoshop. These are usually installed by the user, but they may also be preinstalled

- Files generated by those programmes - e.g. Word documents - as well as imported media files such as photographs or music

When the computer boots up, the operating system is loaded from the hard drive into RAM, and this process is repeated when the user launches applications.

Hard Drives for Macs

Apple has now standardised its entire range of Mac computers onto SSD hard drives. These range in capacity from 256 GB on its MacBook range up to the colossal 8 TB SSD drive available for the Mac Pro, which is aimed at professional content creators and editors.

All current Macs have also been standardised onto the Thunderbolt 3 interface. Some offer a closely related variant, USB 4, which will work with Thunderbolt 3 devices, but which is also backwards compatible with USB 3.2 and 2.0. Therefore, it is important to make sure that external hard drives intended for use with a Mac will work with Thunderbolt 3 and USB 4 ports.

Hard Drives for PCs

Windows has a much more diverse ecosystem than macOS, so if you are a desktop or laptop PC user, you will have a greater selection of internal and external hard drives to choose from. You are only limited by the ports available on your device. However, the highest quality desktop drives are often recommended for quality and longevity.

What Does a Hard Drive Do?

Hard drives store data for later retrieval - specifically the computer’s operating system, the available applications, and all the files generated by that software.

How Do Hard Disks Work?

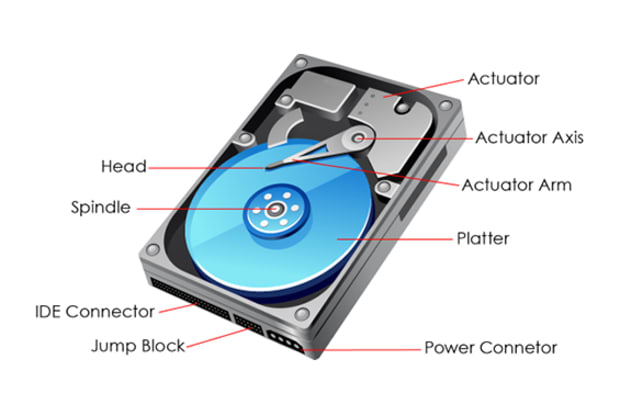

Traditional hard disk drives work via the principles of magnetic data storage. A device called an actuator arm with a read-and-write head attached moves across the surface of spinning magnetic disks called platters to retrieve data stored in different locations. The heads, just nanometres from the surface, read and change the pattern of magnetised particles beneath them. These particles have different magnetic polarities - positive or negative, and these represent either a 0 or a 1 in binary code.

This design means that there is always a delay or lag before information can be retrieved. The arm must move to the correct location on the disk for a specific piece of data, and it may have to repeat this process several times before a particular file or application can be fully assembled in RAM and opened. This lag - called latency - is normally measured in milliseconds but it can climb to whole seconds if the disk is spinning up from a low power rest mode. By contrast, the speed of modern CPUs is measured in nanoseconds. One nanosecond is equal to one million milliseconds.

As each generation of CPU became faster and faster, the gap between hard drive latency and CPU speed grew greater and greater, despite improvements in hard drive technology enabling the platters to spin more quickly. The inherent limitations of HDD technology meant platter revolution eventually maxed out at around 100,000 revolutions per minute (RPM).

Solid-state drives work differently. They rely on much faster flash memory which does not require any moving parts to operate. Data is stored within cells that operate as floating (electronically isolated) logic gates. Logic gates are computational switches that produce a single output from two binary inputs. Electrons interact with these gates, changing their charge from one state to another in a flash. This change in charge rapidly erases the existing data in the cell so new data can be entered. A second gate, called a control gate, regulates the entry and exit of data.

These electrical charges are retained even when the device is not connected to power. For this reason, flash is considered non-volatile memory.

The memory cells themselves are a type of metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistor or MOSFET.

There are two types of flash memory - NOR or NAND, so-called for the type of logic gate they employ. NAND flash is the most widely used and has become the default choice in many familiar devices including USB drives and modern computers. It is less expensive and more capacious than NOR flash.

NAND memory is laid out in grids, called blocks, each made of rows called pages. A typical NAND block varies between 256 kilobytes and 4 megabytes in size. A kilobyte is 1,024 bytes, each byte being a group of eight binary digits.

Flash memory offers an average speed of 1GB per second.

Hard Disk Diagram

The diagram to the right illustrates the structure and labelled components of a traditional hard disk drive.

Image: RS

Flash Drive Cell Diagram

The diagram to the left shows the very different structure of a typical flash drive cell.

A simple cell like this features a MOSFET with two gates. These are the floating gate and the control gate.

Image: RS

Hard Drive Types

There are two types of hard drive - hard disk drives (HDDs) and more modern solid-state drives.

HDDs

HDDs are well-established technology. They rely on a device called an input-output (I/O) controller to direct a read-write arm to the correct location on a spinning platter to retrieve required data.

The principal disadvantage of hard disks is speed. Modern processors are now so fast that HDDs struggle to keep up. The moving parts in HDDs are prone to failure over time.

Advantages of HDDs include:

- Time-honoured technology

- High storage capacities

- Low cost

SSDs

Solid-state drives are more modern technology and consist of an array of data-dense flash memory chips. Although still more expensive than HDDs, they are becoming increasingly standard across devices.

Computers can be configured to store their operating systems in flash memory for high-speed boot-ups, while the remaining data remains on a conventional HDD. This arrangement is called a fusion drive.

The principal disadvantage of SSDs is their high cost, but this is gradually falling as information technology manufacturers increasingly standardise SSD drives.

Advantages of SSDs include:

- High data reading and writing speeds

- Small and lightweight

- Energy efficiency

- Low failure rates

SATA

Serial Advanced Technology Attachment (SATA) is a type of interface used by most modern internal hard drives, whether HDD or SSD.

SATA has become an industry standard because it offers several advantages over older interfaces. These include reduced complexity, smaller cables, higher speeds and the ability to hot-swap (attach or detach without shutting down the computer first).

Internal or External Hard Drive?

External Hard Drives

External hard drives are a diverse range of accessories providing additional storage space for laptops and desktops. These useful devices allow files and data to be quickly and easily stored even when free space on the internal hard drive is limited.

Most external hard drive models are connected to computers via high-speed cables - USB has become the industry standard here. However, some models can connect to the host computer wirelessly. These devices are referred to as network-attached storage (NAS).

Portable Hard Drives

Portable hard drives are small, lightweight external drives that can be configured to act as bootable hard drives with some computer models. The system boots up from the portable drive rather than the internal one. This allows the user to experiment with alternative operating systems - for example, Linux on a Windows machine - or to securely use a third-party computer.

Internal Hard Drives

All modern desktop and laptop computers contain internal hard drives. However, this was not always the case. Early models relied on portable media such as floppy disks or tape drives.

Hard Drive Capacity

The storage capacity of hard drives is measured in bytes. A byte usually consists of eight binary digits of data. This is a very small unit of data, so the smallest quantity normally encountered is the kilobyte (KB) which is 1024 bytes. The more familiar megabyte (MB) consists of 1,024 kilobytes or one million bytes. A gigabyte (GB) is 1,024 megabytes or one billion bytes, and a terabyte (TB) consists of 1,024 gigabytes or one trillion bytes.

Most modern hard drives are measured in gigabytes and terabytes. 500GB of flash memory is now a relatively standard laptop hard drive size, while 1TB is a higher-end option for both laptops and desktops.

Sizes over 1TB can be found in some high-end computers but they are primarily confined to external hard drives. These very high capacity devices are a good choice for the storage of space-hungry files and backups of the internal hard drive in your computer.

Brands

As standard computer components, internal hard disks and external hard drives are manufactured by some of the largest technology firms in the world. These include:

How Much Does a Hard Drive Cost?

Computer hard drives are a standard component and their price has declined dramatically over time as manufacturing and technology has improved. Prices vary by the size of the drive and as newer technology, SSDs are typically more expensive than HDDs.

Our popular products include:

8TB Internal SSD

Samsung MZ 77Q8T0 2.5 in 8 TB Internal Hard Drive. Price each £978.14 (exc. VAT)

1TB External HDD

iStorage diskAshur2 1 TB External Hard Drive. Price each £257.55 (exc. VAT)

FAQs

What is the Role of the Hard Drive?

Hard drives store data, some crucial to the computer’s operation. When a computer starts up, it loads its operating system from the internal hard drive into RAM, enabling the user to begin operating the device. When an application is launched, that is also loaded from the hard drive into RAM ready for use. Additionally, both internal and external hard drives can store documents and media files.

What is the Best Backup Device for Computers?

The best backup devices for computers combine robust external drives with automated software. This will back up crucial data at scheduled intervals without user intervention. Current versions of both macOS and Windows contain automated backup features - called File History on Windows and Time Machine on macOS.

For the external drive, choose a reliable brand producing hardware with a good lifespan to provide safe storage for your data.

What is the Difference Between 2.5 and 3.5 Hard Drives?

These are the two principal sizes of hard drive. 2.5-inch drives are shorter and thinner and so are the default choice for laptop computers, while desktop computers typically feature 3.5-inch drives. The exception is SSDs, which often feature the 2.5-inch form factor even if intended for desktop use.

The names provide only an approximation of the size. A typical 3.5-inch drive would be four inches wide, 5.8 inches long and around 0.8 inches thick. By contrast, typical dimensions for a 2.5-inch drive would be 2.8 inches wide, four inches long and just 0.4 inches thick. They are only about one-quarter of the size of their larger counterparts.

Related Guides

Related links

- SATA Cables – A Complete Guide

- CD, DVD & Blu-Ray Drives

- A Complete Guide to Portable Data Storage

- Western Digital My Passport Portable HDD Storage 2.5 inch 4 TB...

- Western Digital MY PASSPORT ULTRA PORTABLE HDD STORAGE 2.5 inch 5...

- Western Digital MY PASSPORT ULTRA PORTABLE HDD STORAGE 2.5 inch 4...

- A Complete Guide to Socket Sets

- Western Digital WD Gold Enterprise HDD 3.5 inch 8 TB Internal Hard...